Beneath the cheerful buzz of Milan’s canal-side cafes, a Renaissance secret still flows. These waterways were once Leonardo da Vinci’s open-air laboratory, an unlikely stage where an artistic genius was also a pioneering engineer. The Navigli – Milan’s network of canals – quietly shaped Leonardo’s life and ideas in ways few of us expect.

A City Built on Canals

Long before Leonardo’s arrival, Milan was laced with canals that put the landlocked city in touch with distant lakes and rivers. By the 15th century, the Naviglio Grande and other channels carried boats laden with grain, wine, and even massive slabs of marble bound for the new Duomo cathedral. Imagine watching a barge drift by carrying pink-hued marble from Lake Maggiore – this was a common sight! These waterways were the bustling arteries of Milan’s trade and daily life, as vital to the city as roads and railways would later become. Yet in the 1480s, the canal system was still a work in progress. Ambitious dukes dreamed of expanding it further, linking Milan to Lake Como and beyond. The city’s fate, it seemed, flowed with the currents of the Navigli.

Candoglia quarry, source of Duomo’s pink marble. © Roberto Maggioni

The Duke’s Engineer

Into this world stepped a Florentine artist hungry for new challenges. In 1482, a 30-year-old Leonardo da Vinci arrived at the court of Ludovico Sforza (known as il Moro), ostensibly to create art – but Leonardo had bigger plans. He had written to the Duke advertising his skill not just with a paintbrush but with fortresses, machines, and waterways. Why would Milan’s ruler enlist an artist from Florence to tackle engineering projects? Because Leonardo promised something unique: to remake the city’s infrastructure with the same creativity he applied to his paintings. Soon after he arrived, Ludovico put Leonardo to work on Milan’s waterways. We can picture the young engineer trudging along a canal bank with notebooks in hand, studying water levels and sketching clever mechanisms to tame the flow. He examined the existing canals and their crude dams, determined to solve a nagging problem – how to move boats uphill into Milan’s higher-elevation city center.

Leonardo embraced the task. By the 1490s, his talent had earned him an impressive title: Master of Water for the Duchy of Milan. The artist who painted The Last Supper was simultaneously the chief engineer of canals, tasked with turning Ludovico’s grand navigation plans into reality. It’s a testament to Leonardo’s versatility that as he orchestrated biblical scenes on monastery walls, he was also orchestrating the flow of rivers and canals across Lombardy.

Leonardo da Vinci, 19th‑century engraved portrait

Innovation on the Navigli

Faced with the challenge of connecting waterways at different heights, Leonardo pioneered a solution that would change engineering forever. He envisioned a new type of canal lock – essentially a walled basin with gates at each end – to raise and lower boats like an aquatic elevator. Locks of a basic kind already existed elsewhere, but Leonardo refined the concept into something truly efficient. His design used a pair of sturdy wooden gates hinged on opposite sides of the canal and meeting at a slight angle in the middle, forming a V-shape pointed upstream. When rushing water pressed against these closed double doors, their angled shape forced them tighter together, cleverly sealing any gap. Leonardo also added small sliding panels at the base of each gate, allowing water to be let in or out slowly to equalize levels before the gates were opened. In essence, he turned water’s own force into the tool that made the system work safely.

The Duke approved Leonardo’s plans, and soon the city saw results. Under Leonardo’s direction, Milan built a series of new locks along the Navigli – including an important one at San Marco that linked the Naviglio della Martesana to the city’s inner canals. For merchants and travelers, it must have felt like magic: boats could now glide uphill, stepping from one waterway to the next instead of being laboriously dragged over land. It was an engineering marvel ! The once-disjointed canals merged into a connected network, just as Ludovico had envisioned. Its no wonder that nearly all modern canal locks – from the Panama Canal to the Mississippi – still use Leonardo’s double-gate design. The basic mechanics of those distant locks would be instantly familiar to the Renaissance builders at the Darsena harbor.

Mitre lock gates demonstrating V‑shaped double doors © Thomas Holt

The Flow of Inspiration

Working on the canals did more than boost Milan’s economy – it also nurtured Leonardo’s own genius. Day after day, as he measured currents and tinkered with sluice gates, Leonardo deepened a lifelong fascination with water. He believed that water was the driving force of nature and treated it as far more than a mere element; to him it was a muse. His notebooks from these years swirl with sketches of eddies, whirlpools, and even fanciful schemes to reroute rivers. One can imagine him pausing by a flowing canal at dusk, watching the lamplight dance on the ripples, and seeing in that motion the same swirling patterns he would later capture in paint – from the curls of a model’s hair to the turbulent skies in his drawings of storms. The practical lessons he learned taming real canals fed his imagination. Empowered by success in Milan, he even proposed bold new projects in other cities (like diverting the Arno River in Florence) to apply his hydraulic ideas on an epic scale. The Navigli project proved that Leonardo’s futuristic visions could work in the real world, boosting his confidence to pursue ever larger dreams.

There’s a striking human side to this story as well. In solving Milan’s canal puzzles, Leonardo wasn’t sequestered in a studio – he was out on muddy construction sites, collaborating with builders and boatmen to bring sketches to life. He bridged the gap between artist and engineer, between noble and laborer. The sight of workmen hauling stone blocks off barges or blacksmiths hammering iron parts for a lock was not just background scenery to him – it was inspiration. Could the genius who painted the Mona Lisa have been shaped by the grime of manual work and the rhythm of lapping water? In many ways, yes. These hands-on experiences grounded his creativity in practical understanding. They taught him how nature and human ingenuity could intersect, a lesson he carried into countless inventions (and one we can still discern in his art and writings).

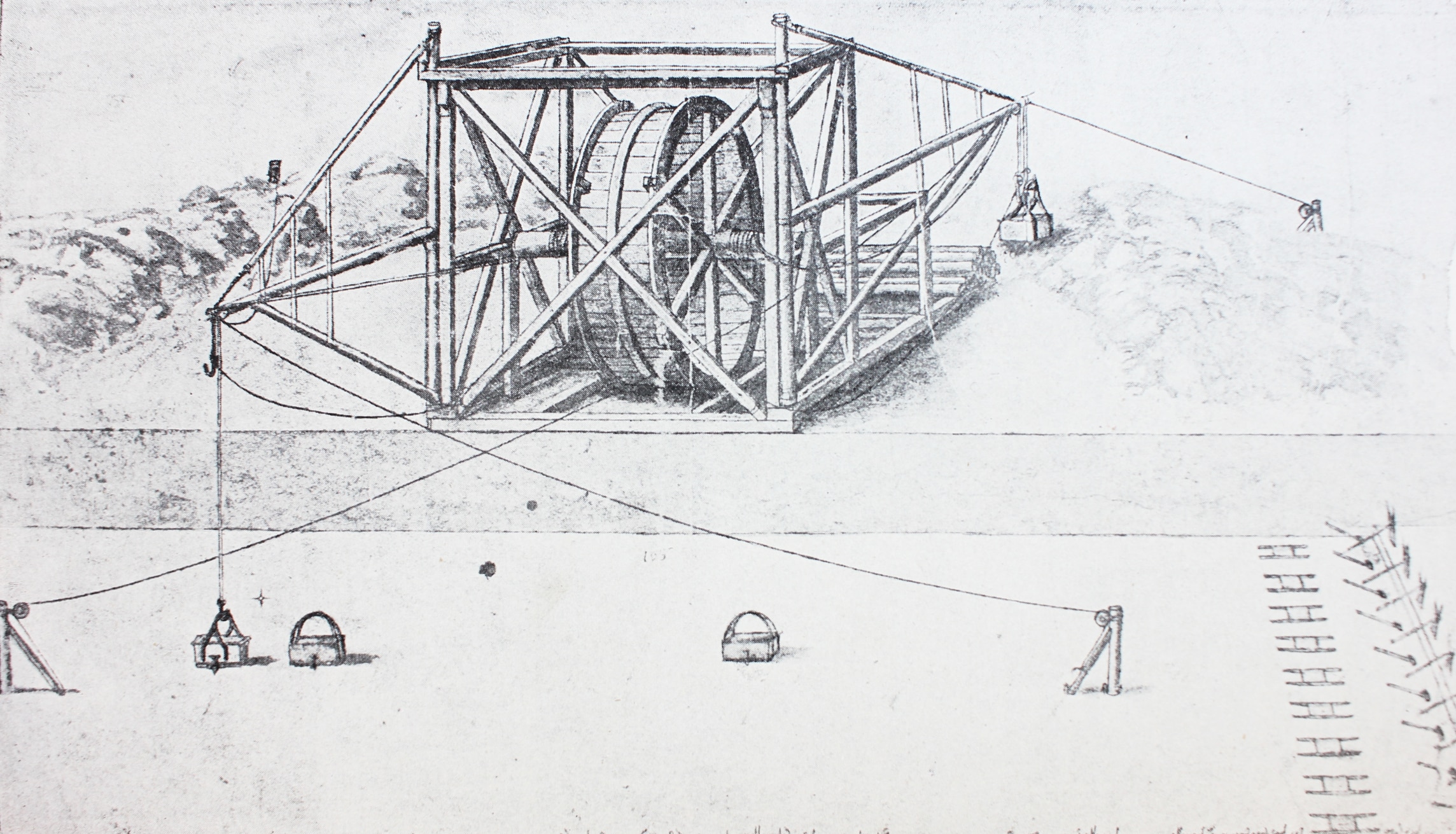

Leonardo’s water mechanism from the Codex Atlanticus © Volodymyr Polotovskyi

Echoes Through the Centuries

Leonardo’s achievements on the Navigli left a lasting mark on Milan. Under his guidance, the city truly became a “water city”, and by 1500 the canal network was nearing its full Renaissance extent. Milanese citizens could boast that their home rivaled Venice – they had a lattice of waterways bustling with barges, and a lively port at the Darsena where inland ships arrived with goods from distant lands. The very marble that raised Milan’s splendid Duomo had navigated through Leonardo’s locks, sailing smoothly into town from quarries miles away. Prosperity flowed in with the water.

In time, however, the currents of history shifted. By the late 19th century, railways and paved roads had outpaced the old canals. The Navigli gradually fell into disuse, and in the 20th century many of these canals were paved over or covered, their waters relegated to underground channels. Today only a few stretches – like the picturesque Naviglio Grande and Naviglio Pavese – remain open to the sky, serving as historic touchstones in a modern city. Tourists and locals stroll along these remaining canals, often unaware that just beneath their feet lies the legacy of a Renaissance genius. Milan has largely forgotten that it was once built on water, or that Leonardo da Vinci helped to build it.

Darsena where Naviglio Grande meets Naviglio Pavese © Brasilnut

Yet the legacy endures. Every canal lock in the world that raises a boat through a change in elevation is a quiet tribute to Leonardo’s innovation. And in Milan’s rejuvenated Navigli district, where cafés and studios now occupy the canal-side buildings, there is still a faint echo of the past. We linger on the brick banks at twilight – perhaps without realizing whose footsteps we follow – and hear the same gentle lap of water against stone that Leonardo would have heard. In the story of Leonardo and Milan’s Navigli, a simple truth emerges: even humble canals can carry a genius to great heights, and the ripples of his work still spread across the world.

Leave a Comment