What traces of Leonardo da Vinci’s genius are hiding in plain sight across Milan’s churches and galleries today? Walk into a dimly lit chapel or a quiet museum hall in that city and you might find yourself face-to-face with a painting that feels like a Leonardo. The soft shadows shaping a gentle smile, the delicate fall of light on curly hair, and the serene poise of the figures – all echo the master’s touch. Yet the name on the plaque isn’t Leonardo da Vinci at all, but one of his followers. These artists, known as the Leonardeschi, were the devoted pupils and imitators who carried Leonardo’s flame. They turned 16th-century Milan into a workshop of innovation and ensured that the great Florentine’s style would live on long after he left. In the story of the Leonardeschi, we discover how a single genius sparked an entire school – and where we can still witness their handiwork today.

Leonardo Founds a School in Milan

Leonardo’s arrival in Milan in 1482 marked a new chapter for the city’s art scene. After years of gaining fame in Florence Leonardo accepted an invitation to the court of Milan’s Duke, Ludovico Sforza, in hopes of greater patronage and projects. The young prodigy from Tuscany – who had trained under the celebrated Florentine artist Andrea del Verrocchio – now stepped onto a bigger stage. In Milan, Leonardo spent the longest stretch of his career (an impressive 17 years from 1482 to 1499) working on grand commissions and drawing eager talent into his orbit. It didn’t take long for local painters to flock to this rising star. The Duke allowed Leonardo to establish a studio with assistants, knowing the scale of work he envisioned (from giant murals to mechanical marvels) required many helping hands. Thus, almost by accident, Milan’s first “Leonardesque” school began to form around the master.

Who were these early Leonardeschi? They were mostly young Lombard artists who either apprenticed directly under Leonardo or gravitated to his revolutionary style. In the late 1480s and 1490s, Leonardo’s workshop buzzed with activity from dawn till dusk. Picture a large, sunlit studio near the Castello Sforzesco: apprentices grinding vivid pigments, stretching canvases, and observing as Leonardo demonstrates subtle brushwork on a Virgin’s face. Its hard to imagine the excitement – and pressure – of learning from a living legend. Among these pupils were talented figures like Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, Marco d’Oggiono, Giovanni Ambrogio de Predis, Andrea Solario, and a mischievous teenager named Gian Giacomo Caprotti (better known as Salaì, “the little devil”). Leonardo even wrote to the Duke complaining (half-jokingly) that he had six mouths to feed in his studio – a testament to how many apprentices he had taken on by the 1490s. We can almost sense the camaraderie and tension in that workshop: youths striving to impress the maestro, assisting him on prestigious projects, and absorbing his every technique.

Virgin and child by Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio (–1516)

Inside Leonardo’s Workshop

Working side by side with Leonardo da Vinci was both a rare privilege and a daunting challenge. Under Leonardo’s tutelage, these students learned far more than basic painting. He exposed them to cutting-edge ideas in anatomy, engineering, and nature study – because Leonardo’s art was inseparable from science. He taught them how to observe reality closely: the subtle gradation of light and shadow (his famous sfumato technique), the anatomy beneath a figure’s skin, and the way distant mountains fade into a bluish haze. The Leonardeschi assisted on Leonardo’s own masterpieces, leaving their discreet mark on works that today are attributed to the master. For instance, when Leonardo painted the Virgin of the Rocks for a chapel in Milan, Ambrogio de Predis likely helped with some background figures and decorative details. During the creation of the monumental Last Supper fresco in Santa Maria delle Grazie, it’s very possible that Boltraffio or Oggiono mixed pigments, prepared the wall, or even painted minor elements under Leonardo’s guidance. In return, the pupils were allowed to copy the master’s compositions and sketches for their own use, a common practice at the time. This hands-on training forged a generation of artists who thought and saw the world a bit like Leonardo did.

Bernardino Luini, Madonna del Roseto (c.1510) – One of the most brilliant examples of the Leonardesque face type in Milan.

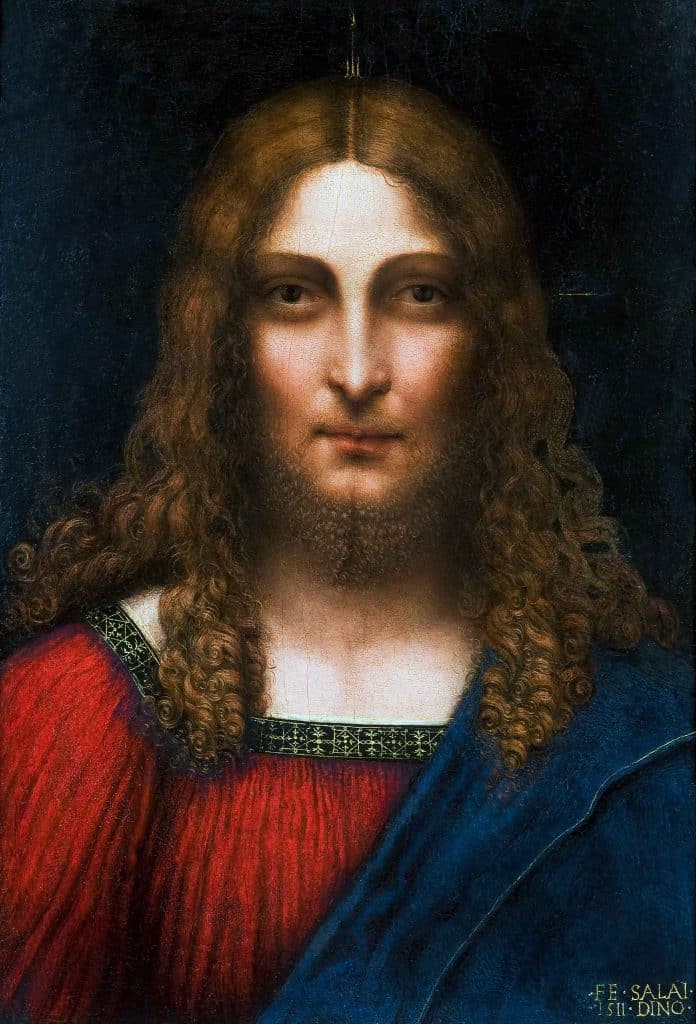

Yet, despite Leonardo’s towering presence, each pupil had his own personality. Salaì, for example, was no angel – his nickname means Little Devil because he was notorious for stealing snacks and causing trouble in the studio. Still, he stayed at Leonardo’s side for years, possibly serving as a model for paintings (some say the curly-haired youth in Leonardo’s St. John the Baptist resembles Salaì’s features). Another pupil, Francesco Melzi, was the polar opposite: a nobleman’s son, polite and devoted, who joined Leonardo’s circle around 1508. Melzi became Leonardo’s most beloved assistant in later years and would eventually inherit the master’s notebooks and drawings. In between these extremes were skilled painters like Boltraffio, who produced gentle Madonnas so like his mentor’s that they were long mistaken for Leonardo’s own work. Bernardino Luini, though not an original apprentice, absorbed Leonardo’s style so deeply that Milanese churchgoers often believed Leonardo himself had painted the beautiful frescoes on their chapel walls – when in fact it was Luini’s brush at work. The Leonardeschi were not carbon copies of Leonardo, but they all shared a common visual language honed under his influence: graceful figures with mysterious smiles, lush curly hair, and dreamy landscapes fading into smoky distance.

Francesco Melzi, Flora (c.1520) – Leonardo’s favourite pupil recreates the master’s knowledge of light in a poetic half-figure.

Head of Christ the Redeemer – https://ambrosiana.it/en/opere/head-of-christ-the-redeemer/

Spreading the Master’s Style

When political turmoil struck Milan in 1499, Leonardo’s world was upended. The invading French armies toppled Duke Sforza, and Leonardo da Vinci left the city, seeking safer horizons. Many of his pupils remained in Lombardy, however, and this is where the Leonardeschi truly came into their own. No longer merely assisting the master, they now began creating independent works – altarpieces, portraits, and devotional paintings – in the master’s manner. In effect, they spread Leonardo’s artistic DNA across northern Italy. How did Leonardo’s style actually travel beyond his own easel? The answer lies in the brush and chisel of these followers. As they took on commissions in Milan and other cities, they naturally infused their work with Leonardo’s techniques and motifs. Walk into a rural church around Lombardy from the early 1500s and you might spot a familiar composition – a Madonna, Christ Child and Saint John arranged in a pyramid, or an angel with the same graceful hand gesture as Leonardo’s – painted not by the great Leonardo, but by Marco d’Oggiono or Giampietrino working in his style. They were like disciples preaching Leonardo’s artistic “gospel” through their own creations.

Giampietrino, The Way to Calvary/Jesus Carrying the Cross- The National Gallery, London.

Some Leonardeschi physically carried Leonardo’s style to new places. Around 1513, the ever-restless Leonardo moved on to Rome and eventually to France (where he would die in 1519 at King Francis I’s court). In his absence, a few pupils went on travels of their own. Cesare da Sesto, one of the finest of the group, journeyed to southern Italy – working in Naples and even Sicily – and there he introduced the soft Leonardesque grace to audiences who had never seen anything like it. Meanwhile, two Spanish painters who briefly collaborated with Leonardo, Fernando Yáñez and Hernando de Llanos, returned to Spain and brought a touch of Leonardo’s Renaissance innovations to the Iberian world. In their altarpieces back in Valencia, we can spot the unmistakable echoes of Leonardo’s inventions (one composition of the Virgin and Child by Yáñez closely imitates Leonardo’s own Virgin of the Rocks, complete with ethereal lighting and rocky grotto). News of Leonardo’s marvels spread across Europe as well. Northern artists like Albrecht Dürer in Germany eagerly sought out Leonardo’s drawings and ideas, incorporating bits of his perspective and anatomy lessons into their engravings. The Leonardeschi, whether by direct teaching or by the example of their works, were the crucial conduits who transmitted Leonardo’s artistic vision far and wide during the early 16th century.

Fernando Yáñez de la Almedina. Collection: The Met.

Perhaps the most literal way they spread his style was by making copies and variations of Leonardo’s masterpieces. Remember the Last Supper – Leonardo’s famed mural was so novel that contemporaries wanted replicas. The earliest copies of The Last Supper, almost as old as the now-faded original, were painted by Leonardeschi such as Boltraffio, Giampietrino, and Cesare Magni. Giampietrino’s full-scale copy of the Last Supper (now in London) has preserved details that time has erased from Leonardo’s own work, proving how faithfully these pupils could emulate their master. Likewise, Salaì and others made small panel paintings based on Leonardo’s compositions – a Saint John the Baptist here, a Madonna and Child there – effectively multiplying the reach of his art. To the Renaissance public, many of whom would never see an original Leonardo, these Leonardeschi works were the next best thing: they disseminated that unmistakable look of Leonardo’s art – the mysterious smiles, the halos of golden light, the naturalistic details – into many hands and places. It’s no wonder that for centuries, quite a few Leonardeschi paintings were misattributed to Leonardo himself. Wealthy collectors and museums, hoping to own a genuine da Vinci, often snapped up a beautiful Madonna or portrait only to later learn it was by a follower. One striking example is the painting Flora, a sensual portrait of a woman with flowers: once hailed as a lost Leonardo, it was eventually credited to Francesco Melzi, the master’s gifted protege. Such cases show how seamlessly the pupils could blend their art with Leonardo’s spirit – sometimes fooling even the experts.

The Leonardeschi Legacy Today

Five hundred years later, the legacy of the Leonardeschi still surrounds Milan – and indeed much of the art world – if you know where to look. The works of these artists may not be as famous as the Mona Lisa, but standing before them can feel like encountering Leonardo’s echo. So, where can a curious art lover see the Leonardeschi on display? Fittingly, many of their masterpieces remain in Milan, the very city that nurtured their talents. A tour of Leonardeschi landmarks might start at the Castello Sforzesco, where the castle’s art museum holds gems like Madonna and Child with Saints by Marco d’Oggiono – a painting inspired by Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks, with the same pyramidal composition but a softer, more muted glow. Nearby, in the Pinacoteca Ambrosiana, you’ll find a rare panel by Salaì (a Head of Christ the Redeemer with Leonardo’s unmistakable gaze) and several tender Holy Family scenes by Bernardino Luini. In fact, the Ambrosiana gallery is special: it not only displays Leonardo’s own Portrait of a Musician but surrounds it with works by his pupils, allowing us to compare master and followers side by side.

Leonardo da Vinci – Portrait of a Musician – Pinacoteca Ambrosiana

At Milan’s premier art museum, the Pinacoteca di Brera, the Leonardeschi practically take over an entire room. Here, almost every major student of Leonardo is represented: Boltraffio’s luminous Madonna of the Carnations, Cesare da Sesto’s idyllic Madonna and Child under a Tree, Luini’s charming Madonna of the Rose Garden, and even an anonymous spectacular altarpiece called the Pala Sforzesca (attributed to a “Master of the Sforza Altarpiece,” likely a close Leonardo associate). It’s like a family reunion of Leonardo’s circle, each canvas reflecting a facet of his style – and yet showing the personal twists each artist added. A short stroll away is the Poldi Pezzoli Museum, a treasure trove of Renaissance art that includes Andrea Solario’s moving Ecce Homo (Christ with the crown of thorns, painted with a translucence that clearly nods to Leonardo’s study of light on skin) and a tender Madonna and Child by Boltraffio. This museum even holds a tiny bronze statuette of a warrior on horseback that scholars think came from Leonardo’s workshop – a rare three-dimensional glimpse into the projects Leonardo and his team once explored for the Duke. Finally, the Milan Diocesan Museum offers insight into how Leonardeschi art adorned local churches: here you can see Giampietrino’s Christ Carrying the Cross, an emotional work thought to be based on a lost Leonardo drawing, and a late altarpiece by Marco d’Oggiono that reinterprets the composition of Leonardo’s Virgin of the Rocks for a new generation of worshippers.

Andrea Solario, Ecce Homo

Milan isn’t the only home for Leonardeschi works – their paintings have traveled over centuries, finding homes in museums around the globe. You’ll encounter Leonardeschi surprises in the most prominent galleries: a radiant Luini Madonna hanging in the Louvre, a portrait by Boltraffio in Washington D.C.’s National Gallery, or a graceful Leda and the Swan copy (after a lost Leonardo) by Cesare da Sesto in the Naples Museum. Each of these works carries a bit of Leonardo’s soul. Viewing them, we feel a connection not just to the pupil who painted it, but to the genius who originally inspired it. The Leonardeschi may have started as students imitating a master, but their collective legacy is an artistic phenomenon in its own right – one that bridges Leonardo’s singular brilliance with the broader story of Renaissance art.

Giampietrino – Leda and her Children

In the end, the story of the Leonardeschi is a human one: bright young artists drawn like moths to Leonardo’s flame, doing their best to honor his vision while forging their own paths. Some remained lifelong collaborators; others branched out geographically; all contributed to the diffusion of a style that might otherwise have vanished when Leonardo died. Their paintings and frescoes allow us, even today, to step into Leonardo’s world. We can stand before a Leonardeschi canvas and sense, in the gentle shadows and enigmatic smiles, the lingering presence of the master who sparked it all. Without the Leonardeschi, Leonardo’s impact would have been far more limited – but thanks to this Milanese school of art, his influence blossomed across generations and borders. As we wander through a gallery or a church and suddenly catch a whiff of Leonardo’s style in an unexpected corner, we’re experiencing the silent, enduring echo of Leonardo da Vinci – carried by the brushes of the Leonardeschi. And that is perhaps their greatest masterpiece of all.

Leave a Comment