Imagine standing before Milan’s majestic cathedral and discovering that its crowning dome could have been designed by Leonardo da Vinci. It sounds like a fantasy, yet in the late 1480s this almost became reality. The Duomo’s great tiburio – the massive central tower and dome over the crossing – was the unfinished puzzle of its age. Leonardo, ever the visionary, stepped forward with an audacious plan to solve it. Why then does the cathedral’s skyline today bear no trace of Leonardo’s dome? The answer lies in a Renaissance tale of ambition, innovation, and the weight of tradition.

A Cathedral’s Unfinished Crown

By the 1480s, Milan’s Duomo di Milano had been under construction for nearly a century. This towering Gothic cathedral, begun in 1386 under the patronage of Duke Gian Galeazzo Visconti, had already become a forest of spires and flying buttresses. Yet at its heart loomed an open void: the tiburio, or dome crossing tower, remained incomplete. Building a stable dome over such a vast space was a daunting engineering challenge. Earlier architects had tried solutions and even called in foreign experts – at one point a renowned German master builder was consulted – but the problem persisted. The Veneranda Fabbrica (the cathedral’s construction guild) organized design contests and committees, searching for the genius idea that could safely crown the cathedral with glory. By 1487,the unfinished dome was not just an architectural issue but a symbol of Milan’s pride on hold, waiting for a brilliant mind to deliver a cappella worthy of the heavens.

Gothic flying buttresses of the Duomo

Duomo of Milan

A Genius Joins the Challenge

Into this scene entered Leonardo da Vinci, who arrived in Milan in the early 1480s seeking new horizons. Leonardo was already famed as an artist, but he had also pitched himself to Milan’s Duke Ludovico Sforza as an engineer and architect. The Duomo’s dome project was his chance to prove it. In 1487, when a new competition was announced to design the cathedral’s tiburio, Leonardo threw his hat in the ring. He was in exceptional company: established architects like Donato Bramante, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, and local masters including Giovanni Antonio Amadeo and Gian Giacomo Dolcebuono all prepared proposals. Unlike veterans such as Bramante (already respected for church designs), Leonardo had never built so much as a shed – but that hardly stopped him. With unquenchable curiosity, he immersed himself in the problem. We find him poring over the cathedral’s records and earlier blueprints, even jotting notes on scrap paper recycled from old account ledgers. He studied what previous builders had attempted, determined to avoid their pitfalls. The young Leonardo we encounter here is part artist, part detective, learning everything he can about this leviathan of a building before daring to redesign its crown.

Leonardo’s approach to the tiburio was as much intellectual as it was artistic. He believed an architect must understand the fundamental “rules” of construction – an idea he gleaned from Renaissance humanists like Leon Battista Alberti and the ancient wisdom of Vitruvius. In a letter to the cathedral officials that accompanied his design, Leonardo waxed philosophical about architecture. He spoke of ensuring symmetry and conformity with the rest of the edifice, stressing that any new dome must “correspond” to the building’s proportions and spirit. This was no mere sketching exercise for him; it was a chance to demonstrate that sound engineering and beauty went hand in hand. We get the sense that Leonardo saw the tiburio not just as a technical puzzle, but almost as a living organism whose final form had to grow naturally from its existing bones.

Leonardo da Vinci monument at Piazza della Scala

Drawing Board of a Visionary

So what did Leonardo actually propose? In the winter of 1487–1488, he translated his ideas into reality – at least in miniature. He spent months drafting and refining plans for the dome. His notebooks (including the famed Codex Atlanticus) reveal that he explored a remarkable variety of designs. On some pages we see sketches of an octagonal dome (reflecting the cathedral’s eight-sided crossing), reinforced by what looks like a ring of flying buttresses for support. On others, he toyed with a circular drum or even a double-shell cupola inspired by Brunelleschi’s dome in Florence. Its as if his mind ran through every possible permutation: Gothic ribbed vaults, classical geometries, mix-and-match combinations of arches and buttresses. This prolific brainstorming shows Leonardo’s inventiveness at full tilt.

Ultimately, Leonardo settled on a particular vision to present officially. Following tradition, the Fabbrica required a scale model – a detailed wooden maquette – of each serious proposal. Leonardo obliged, working with skilled carpenters to build a model of his dome design. Historical records tell us that by January 1488 his wooden model was completed (he even received a payment of 56 lire for his efforts, tangible proof that he had skin in the game). We can imagine this model: a beautifully crafted mini-dome, perhaps showing off Leonardo’s penchant for symmetry and clever structural bracing. He likely included elegant decorative elements as well, like a lantern tower atop the dome to cap it off. One anecdote from his sketches: tiny pinholes and fold lines on the drawings suggest he used a mirroring technique to ensure perfect symmetry – literally folding his paper and pricking through to transfer design outlines. Such details hint at how meticulously Leonardo pursued an ideal balance in the design.

When the model was unveiled to the cathedral authorities, it must have been a show-stopper. Here was the polymath Leonardo da Vinci’s take on how to complete Milan’s grandest monument. His design promised not only to solve the structural challenge of spanning the huge crossing, but to do so with style. We can almost see Leonardo at the review meeting, explaining how his dome would distribute the enormous weight safely down the cathedral’s piers, all while adding a touch of Renaissance harmony to the Gothic silhouette. It was bold, ingenious, and backed by careful study. Yet what happened next shows that even the greatest of minds can hit a wall.

Too Bold for Its Time

The board of judges – a mix of master builders, officials, and perhaps the Duke’s delegates – examined Leonardo’s model alongside others. They compared, debated, and scrutinized every detail, for the fate of the Duomo rested on this decision. In the end Leonardo’s ambitious design was deemed too complex. The exact reasons were not recorded in detail, but we can surmise what might have worried them. Perhaps his plan, for all its brilliance, appeared too difficult or costly to actually construct with the methods available. Maybe the intricate support system he envisioned raised concerns about stability or deviated stylistically from the cathedral’s established Gothic character. One chronicle hints that the proposal was just “too fantastical” for the practical masters. The irony is palpable – the very qualities that made Leonardo’s design innovative also made the traditionalists on the committee break into a sweat.

When Leonardo received the verdict, he was not pleased. The Fabbrica did not outright dismiss him; instead, they reportedly asked if he would adjust his design to address their concerns. Essentially, they wanted a toned-down, simplified version of Leonardo’s dome. But Leonardo was not one to compromise easily on a grand vision. In a bit of Renaissance drama, he refused to revise his proposal. We can imagine his frustration: after months of immersion in this project, Leonardo believed in his solution and wasn’t about to water it down. Consequently, he withdrew from the contest (or was edged out, depending on the telling). While other architects might have tried to haggle or rework their models to please the panel, the maestro from Vinci essentially took his model and went home. It’s hard not to feel a pang of sympathy here – even a genius like Leonardo had his work sent back to the drawing board by a committee that ultimately didn’t bite.

The Dome That Rose Without Leonardo

With Leonardo’s exit, the cathedral’s tiburio challenge passed into other capable hands. The design eventually selected was a blend of ideas, spearheaded by two Lombard architects who had long been involved in the project: Giovanni Antonio Amadeo and Gian Giacomo Dolcebuono. Their solution, notably, included an octagonal dome reinforced by eight heavy buttress-like supports – a concept not unlike one of Leonardo’s sketches, albeit executed in a more conservative fashion. Construction moved forward in the 1490s, and by 1500 the Duomo’s once-gaping crossing was safely surmounted by a grand dome of stone. Under the patronage of Ludovico Sforza (and continuing even after his fall from power), the octagonal cupola took shape and was completed in the first years of the 16th century. Inside, it was later adorned with rows of statues of saints and prophets, gazing down from the heights. Outside, the structure kept a restrained Gothic appearance. In fact, aside from a small elegant spire known as “Amadeo’s little spire” added around 1507 – a touch of Renaissance flourish atop the dome’s lantern – the cathedral’s exterior revealed little hint of the new classical ideas. The dome harmonized with the rest of the medieval church as if it had always been there.

Milan Cathedral on Piazza del Duomo

Meanwhile, Leonardo da Vinci moved on to other endeavors. In the 1490s he poured his energies into painting The Last Supper and devising engineering marvels for the Duke. One of those projects was a colossal bronze horse statue for the Sforza – another grand idea that, like the tiburio, would remain unbuilt (war would reduce his giant clay horse to rubble before it could be cast in metal). It seems Milan offered Leonardo triumphs in art but also a fair share of dashed architectural dreams. Yet, there’s a footnote to this story: some historians speculate that Leonardo’s tiburio concepts might have quietly influenced the final design after all. The chosen architects were aware of each other’s models and reports. It’s possible that certain innovative reinforcement techniques or proportions in the finished dome were indirectly inspired by Leonardo’s research. If so, it was a silent victory for him – one buried under layers of stone and credit given elsewhere.

Legacy of a Lost Masterpiece

Leonardo’s unbuilt dome for the Duomo remains one of history’s great “what ifs” in art and architecture.On one hand, the cathedral we see today is a magnificent accomplishment in its own right – a testament to Gothic tenacity that ultimately solved its engineering dilemma without Leonardo’s help. On the other hand, one can’t help but wonder how a Leonardo-designed dome might have altered the skyline of Milan. Would the Duomo have a subtly different silhouette, perhaps capped with a more pronounced lantern or adorned with Leonardo’s signature geometric patterns? Would a daring Renaissance dome atop a Gothic body have been a beautiful marriage of styles or an odd mismatch? These questions tease the imagination of Leonardo enthusiasts and art historians alike.

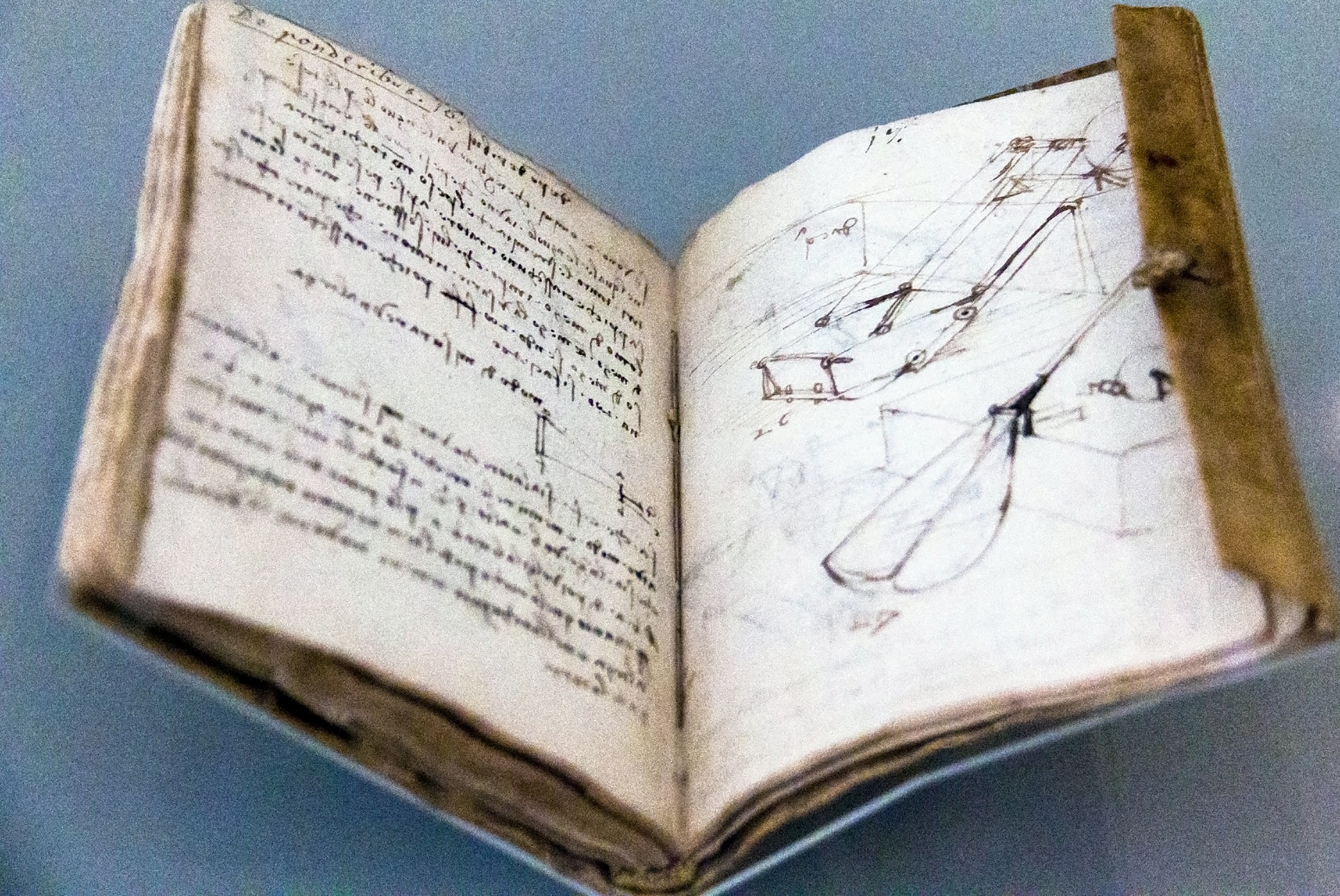

What we do know is that Leonardo’s tiburio project has not been forgotten. His sketches for the dome, preserved in notebooks like the Codex Atlanticus and Codex Trivulzianus, have been studied and even used to create digital reconstructions of his intended design. In recent years, the Museo del Duomo in Milan has showcased these drawings and the story behind them, reintroducing Leonardo’s model to the very site it was meant for. Visitors can see the delicate lines he drew, the careful notes he made in his dense mirror-writing, and the boldness of his vision leaps off the page.

Leonardo’s notebook, Codex Forster, manuscript pages

It’s a powerful reminder that the Renaissance was full of bold plans and that not every genius idea found its way into stone. In the end Leonardo’s unbuilt dome teaches us something profoundly human about even the loftiest genius. It highlights the push and pull between innovation and convention: the visionary inventor versus the cautious builder. The Duomo’s tiburio was completed the old-fashioned way, through consensus and incremental improvement, rather than a single revolutionary leap. Leonardo, for all his unparalleled brilliance, had to accept that this was one masterpiece he would not realize. And yet, the very fact that he tried – that he sketched, calculated, and argued for a new way to finish the great cathedral – enriches the saga of the Duomo. It adds a chapter where art and science nearly took a daring detour.

Standing in Milan today, we gaze up at the marble vaults and can almost sense Leonardo’s ghostly blueprint hanging in the air, a dome that never was. It’s a subtle part of the cathedral’s aura – the knowledge that its completion was not inevitable, but hard-won through debate and dreams. In that story, Leonardo da Vinci’s proposal for the Duomo’s tiburio shines as a brilliant, if unrealized, star. It reminds us that even in failure, great ideas endure: inspiring, instructive, and forever capturing our imagination, much like the Mona Lisa’s unknowable smile carved into the skyline of history.

Leave a Comment